#73 Fake it ‘till you make it

“We think of visionaries and fraudsters as polar opposites. In reality, just like Newton, many of today’s great entrepreneurs have some characteristics of both.”

— Bethany McLean in the New York Times

“…reality is just a vector in Hilbert space….”

— Sean Carroll, in conversation with Jody Azzouni

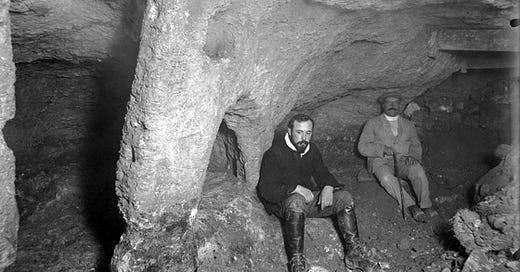

In the early 20th century, a British aristocrat and a Finnish scholar teamed up with a motley crew of adventurers to unearth the Ark of the Covenant. The scholar, Valter H. Juvelius, had somehow figured out the whereabouts of the Covenant in a tunnel below Jerusalem. Unfortunately, he didn’t have the resources, courage, or connections to dig for it in late Ottoman Jerusalem. By the account of Simon Sebag Montefiore — in whose book Jerusalem I discovered this story — it wasn’t exactly a safe place for digging up ancient relics. So, Juvelius needed friends.

Captain Montagu Brownlow Parker was such a friend. Charming, rich, a veteran of the Boer War, Parker had what it took to make this happen. Still, they needed money. Lots of money. Parker got tons of people to invest millions in today’s currency to fund the expedition. What would these investors get in return? A piece of the immense value of the Covenant.

Once in Jerusalem, the crew’s faulty intel, lack of experience, and exorbitance failed to produce the Covenant. Increasingly desperate, Parker’s methods became philistine. Eventually, he even dug underneath the Dome of the Rock, bribing officials and tricking guards. When discovered, the uproar over this sacrilegious act brought the world to the brink of a holy war.

Surprisingly, the episode blew over, and it doesn’t seem Parker ever paid the price (or investors) for his failed scheme. Instead, he continued to be in service for the British Empire. The Ark of the Covenant has never been found, and Parker is largely forgotten.

I spend a lot of time telling stories to change people’s behavior. I believe stories have great power. I also think all good stories are essentially made up, full of lies. Reality often isn’t good enough to fulfill the functions a story can have. In The Things They Carried, Timothy O’Brien writes: “A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done.”

If you want to change the world, you have to bend the truth.

This being the first week of a new year, many of us have bent the truth to change the world. What are New Year’s resolutions other than deliberate lies to make us feel better about the uncertainty that lies ahead?

This week, Elizabeth Holmes, founder, and former chief executive of Theranos, was found guilty on four out of 11 charges of fraud. Holmes’s story is like Parker’s, except that she is not a colonial aristocrat (and man) and will likely have to suffer the consequences of selling a dream that, in the end, proved impossible.

For those of you who haven’t been following the case, Theranos promised advanced blood-testing technology but failed to deliver. Holmes’s incredible talents and work ethic obscured its lack of substance and helped it reach a 9 billion dollar valuation. But, of course, this being Silicon Valley, selling something that doesn’t exist (yet) is not uncommon. Holmes was unlucky in that her hand was forced before she could, somehow, make it work. She tried to settle but couldn’t avoid having charges being brought against her. Now she faces up to 80 years in prison.

In a brilliant NYT essay, Bethany McLean warns against reading too much in the case:

“I’m not so sure there’s any larger message in the Theranos saga. A brief history of prosecutions of suspected white-collar criminals — or the failure to prosecute them — shows that what happens in one case doesn’t mean that much for other cases. Where juries, or even would-be prosecutors, draw the line between the Newtons and the P.T. Barnums, the visionaries and the fraudsters, the overly optimistic and the outright liars strikes me as haphazard, dependent on each set of circumstances, as well as on the ineffable mood of the world at large.” (source)

However, there is a confirmation of something in this case: Telling a story can have serious consequences. While you need to bend the truth, however slightly, doing this can be problematic.

Holmes’s case reminded me of the somewhat different yet similar case of Anna Sorokin/Delvey. Sorokin is another storyteller whose talents weren’t appreciated by all, likely because she used her skills to have others pay for her lavish lifestyle.

In 2018, Jessica Pressler wrote an excellent long read about the rise and fall of the enterprising trickster Sorokin. She describes her lifestyle and ideas through the people that met her and benefitted from her. Pressler’s pen makes Sorokin’s life seem desirable, and the story she tells appears necessary to achieve the dream she pretends to chase: a high-class private club.

“Through her connections, she’d befriended Gabriel Calatrava, one of the sons of famed architect Santiago. His family’s real-estate advisory company, Calatrava Grace, had helped her “secure the lease,” she informed people, on the perfect space (…). The heart of the club would be, she said, a “dynamic visual-arts center,” with a rotating array of pop-up shops curated by artist Daniel Arsham, whom she knew from her Purple days, and exhibitions and installations from blue-chip artists like Urs Fischer, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Tracey Emin.” (source)

Is this visionary or fraud? Did Sorokin bend the truth or simply tell a different reality. As Pressler states, “Some people raised their eyebrows at the grandiosity of this plan, but to others, it made sense, in a New York kind of way.” Is this different from the storytelling needed to turn any idea into reality? Of course, you could argue that Sorokin’s self-enriching is uncouth. Still, outrageous self-enriching didn’t send WeWork’s Adam Neumann to jail. Holmes, in turn, hasn’t been enriching herself at all.

Also, if Sorokin’s ambition was genuine, her lifestyle may have been a prop to tell the story in the first place. Much like the first step in running 750km in a year (a thing I hope to do) is dressing up in the right running gear.

Suppose you’re interested in Anna’s story and want to judge for yourself. In that case, Netflix will premiere a mini-series about her in February.

It was interesting, albeit intellectually challenging, to wrap up this week with a beautiful conversation between one of my favorite podcasters — Sean Carroll — and philosopher Jody Azzouni about what is real.

Azzouni gives some characteristics of what it means to be real. For example, things that are real are independent of us. Which means not a single story we tell is real. So the Ark of the Covenant isn’t real, Indiana Jones isn’t, groundbreaking blood-testing technology is not real, and your new year’s resolutions are neither.

When Carroll, a theoretical physicist, mentions his research, which found that reality is a vector in the Hilbert space (i.e., a mathematical concept), Azzouni challenges this by stating that we have to resist the urge to think that, “If I get a characterization of something and that characterization is empirically on the money, that’s evidence that everything that characterization talks about, mathematically and otherwise, exists.”

Another characteristic of what is real is that science can tell us what is real. But, alas, to prove that science is indebted to tools such as mathematics, which may very well not be real because the only thing that is real is independent of us, and mathematics often isn’t.

The one thing that stood out for me most in the conversation is that to make something real, we have to commit to it. I hope I understood this right. If we say we believe in something — say a particular idea or law — we have to commit to the framework in which this something exists. The Ark of the Covenant is real if you’re genuinely committed to that part of Christianity, history, or archeology. A fancy New York club is real if you commit to the culture that enables these clubs. Clearly, when you get more people to commit to the same framework, it becomes more true.

The lesson for new year’s resolutions? Commit! The more you commit to the framework they’re part of, the likelier they’ll become truths.

As always, thanks for reading, forwarding, replying. This newsletter does not exist independently of you, so only because of you is it real. Thanks for making it so. Have an excellent 2022, and I hope to hear from you often!

All the best,

— Jasper