#7 Cultural language

Congratulations to Merlijn Twaalfhoven, whose inspirational book is available for pre-order now (in Dutch but with a translation upcoming). Merlijn is a composer and musician who has worked worldwide on large, often collaborative projects that bring people together and make the world a better place. His book describes his experiences working on socially engaged art projects and provides guidance to people who want to make culture part of sustainable development. I had the honor of reading an almost finished version of the book last week.

I read It’s up to us by Merlijn Twaalfhoven breathlessly, from start to finish. Merlijn is a gifted storyteller with a keen eye for the details that bring to life the unique situations in which he finds himself through his art and music. From Syria to Zaandam and Cyprus, it always feels like you are there yourself.

I know from experience that the artist mindset for which Merlijn has written a fiery argument is applicable in business, government, education, and wherever we are confronted with complex problems. So this is also a book for anyone who wants to take responsibility for themselves, their environment, and the world. And while the writing prompts the reader to awaken the artist within, it is not a pedantic self-help book. On the contrary! I have become inspired and enthusiastic by the book to do more with art in my life and use the power of art more often to make the world a more beautiful place.

In a small country like the Netherlands, pre-orders help get a book in the bookstores and read by more people, so if you read Dutch (it’s close to German, Danish, Swedish, and ‘Norwegian’), consider pre-ordering now.

Thank you so much for subscribing to my newsletter! I cannot begin to tell you how much I appreciate your being here. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can easily do so in the footer of this email.

We’re living through the longest heatwave in Dutch recorded history. For once, the climate change deniers are quiet, silenced by their air conditioners and lethargy in the face of change. We may learn from the Japanese honey bee, which can defeat the killer hornet because of its superior organization and slightly better ability to take heat. 25 September is the next global climate strike in which #MuseumsForFuture will also play a role. This also happens to be SDG Action Day. With Stichting 2030 and Leiden4GlobalGoals, we’ll be organizing a range of activities in Leiden.

This week I should have been a volunteer at Sail Amsterdam. Sail is a five-yearly gathering of tallships that attracts hundreds of thousands of people from around the world to Amsterdam. I’d volunteered for the hospitality team to practice my languages on unwitting tourists. Alas, Sail was canceled due to COVID-19. We’ll have to wait another five years to celebrate this nautical party (which then coincides with the 750th birthday of Amsterdam). Even though I didn’t work for them, I still got my crew shirts and cap, all in organic cotton. Thanks!

“As other languages had entered his life, Watanabe became aware of the extent to which his mother tongue limited the possibility of improvisation, of meandering through a sentence in search of a point.” (From Fracture)

My native tongue is Dutch, which spoken by some 29 million people. As you have no doubt experienced, the average Dutch person you’ll meet abroad speaks another two or three languages, often with a strong accent, and often less well than they think. When I was learning Spanish, I remember reading La Ciudad de las Bestias by Isabelle Allende. The word ‘temer’ (to fear) regularly appears in the book, which I didn’t know and assumed to be close to ‘tener’ (to have). I then introduced it, erroneously, into my everyday spoken language. “Do you fear a bottle of water?”

While these mistakes can create humorous situations in natural languages, the risk of misunderstandings in cultural languages can be much more severe. This year, I heard an interview with the Dutch researcher Peter Henk Steenhuis and later read a book by his hand. In it, he shared an anecdote about the impact of cultural language. He asked a group of students at a vocational school whether they worried about stress or competition. No response. After some querying, one student finally responds she doesn’t really have an opinion about that. Why not? Because the words are not part of her vocabulary. Stress is not part of her culture, so she cannot be stressed by her work.

This week, a museum may have fell victim to a similar cultural language misunderstanding. The Amsterdam-based Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic) had its municipal funding application for the next four years rejected. By and large, the committee evaluated the museum positively. A damning evaluation of their approach to diversity and representation may have sealed their faith. Reading the assessment, I strongly feel the committee and the application writers of the museum use different cultural languages to talk about similar ideas. For instance, the committee judges that the museum uses too careful vocabulary when discussing diversity.

The Our Lord in the Attic Museum is housed in a seventeenth-century building with a fully functioning Catholic church hidden in the attic. The church was a sanctuary for Catholics who, at the time, couldn’t profess their faith openly. The church was well known to the authorities, which adds to a story of religious tolerance and openness to other ideas. Although a visit is no doubt a historical experience, its story is of openness to differences. To me, it feels harsh to judge it for using careful words when discussing cultural diversity. I have often found that those people who talk about diversity quietly and with humility understand its challenges and necessity much better than those who pay loud lip service to the popular terms of the moment.

My friend Paul Mertz — whom I tend to call the Dutch Don Draper — tirelessly advocates for the use of language that everybody understands. His newsletters tend to be an overview of obtuse sentences and ideas and recommendations to say the same thing in a way people understand. He also encourages young people to chose language as a profession. All our ideas are communicated in words; it is a pity they are misunderstood so often.

Paul also collects words. Currently, he has built a growing collection of over 500 Dutch words related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Just in case you’re working on learning Dutch, they’re an incomparable list to learn both the natural and cultural languages.

This week, I didn’t write about the promise of torrential rain, education, baking a lion cake, a last visit to the zoo, and working at night. I may do so next week, but I think there will be new things to discuss. Thanks for being here, and remember, I will always reply to emails, so feel free to reach out with questions, comments, or requests. You may do so in English, Spanish, Dutch, German, HTML, Python, or CSS.

Thanks again!

— Jasper

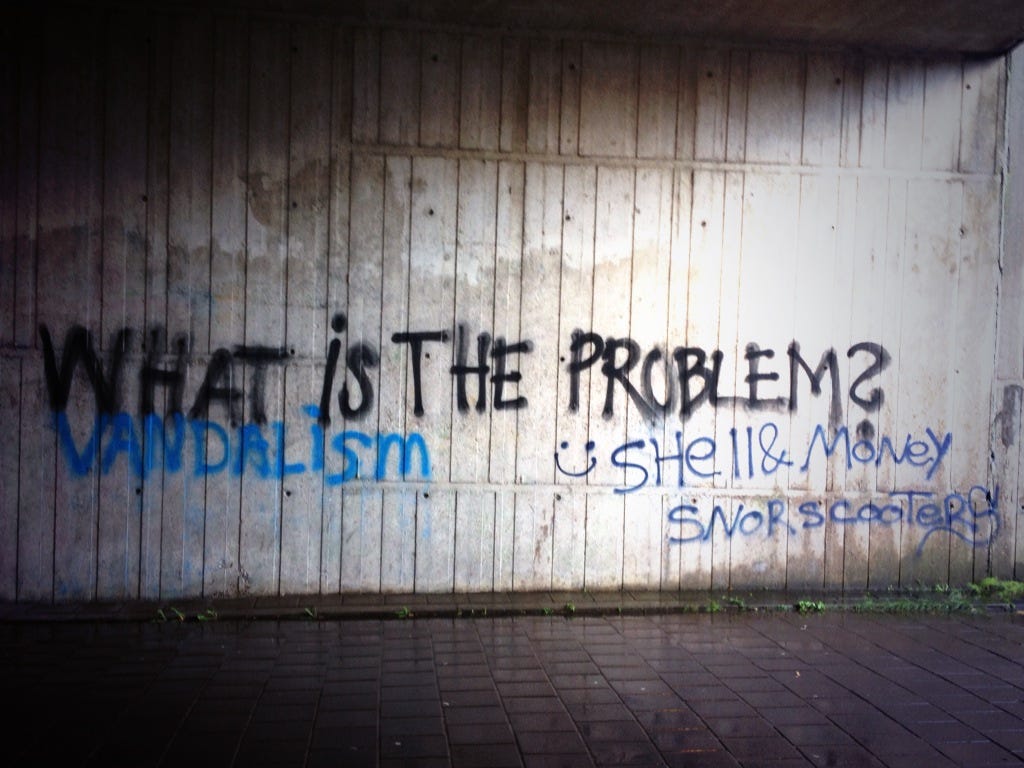

Cultural language on Amsterdam’s streets.