#28 Definitions

This week brought a new chapter in the hottest story in museums in years: the discussion about the new museum definition. ICOM announced a new participatory process. I had missed the new methodology. At first glance, it is over-designed and thereby obfuscates the profound issues with the definition discussion. Full disclaimer: I didn’t think a definition discussion is what museums needed before Covid, BLM, and the 6th of January. I think it needs one even less now.

Hello and welcome to my regular irregular update! I thought I’d start in medias res for a change, to trick you into reading about what may be the dullest thing in the universe: definitions. Years ago, I committed to starting an immediate daydream when I hear the words “let’s first talk about definitions.” Here we are. But I promise an intrigue, hairy things, and two definitions at the very end, so please stay with me.

For my readers whose knowledge about museums comes mostly from The Thomas Crown Affair, a quick summary of what is going on. Museums have a definition (“a statement of the exact meaning of a word”), which is useful because it delineates their position in society. The current definition was agreed upon in 2007 and is mostly descriptive. It is a good definition.

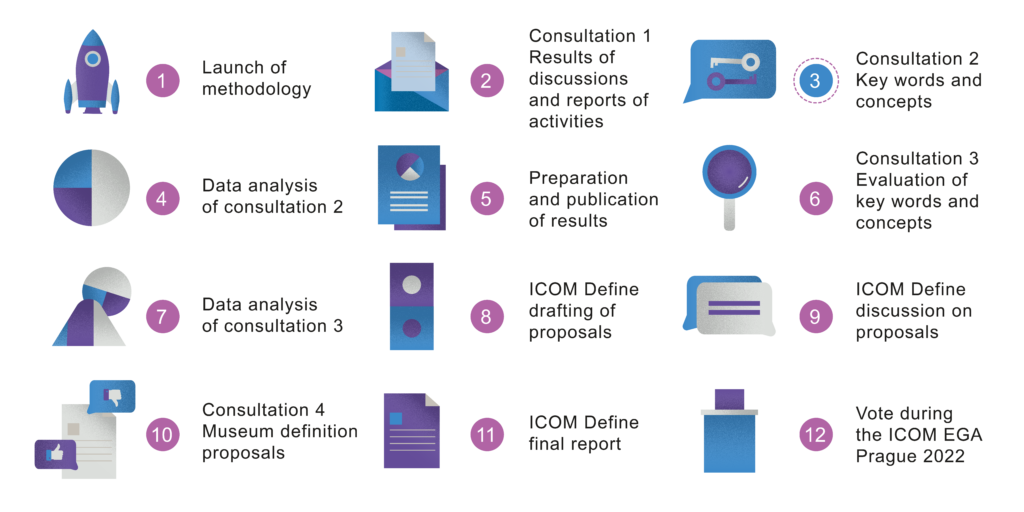

Museums increasingly didn’t recognize themselves in words from 2007. So ICOM, the international council of museums, started an opaque process to come to a new definition. The result of this effort was a perfect case of design by committee. Instead of a concise description, the new definition was a manifesto that called for museums to be polyphonic spaces for social justice, global equality, and planetary wellbeing (and more). It received near-universal scorn and was rightfully voted down.

ICOM has now developed a new methodology to come to an acceptable definition. However, the question remains whether a definition is a solution to the problems with the old definition. As I argued before, I think what museums are looking for is a vision, a compelling story about why they exist in a rapidly changing world. Stay with me because this is not merely a museum story but a cautionary tale for everyone struggling to find their place in 2021 and beyond.

“A vision is a conversation about the future. A vision tells a story about why museums exist and what the world would miss if there are no museums. Such a story is very different from a definition. It doesn’t describe what a museum is, but outlines what a museum can be, can do, and can add to the world.”

Although visions are often communicated widely, their primary purpose is internal. A good vision energizes and empowers people to give their best and be the best they can be. Libraries, for instance, promote “literate, informed and participative societies.” Definitions, on the other hand, work externally. They explain to people who’ve never set foot in a museum what it is. Few people care about a vision that is not theirs.

To drive that point home, McDonald’s vision is “to move with velocity to drive profitable growth and become an even better McDonald’s serving more customers delicious food each day around the world.”

A vision does not change anything. It gives direction. Goals, in turn, set the pace to achieve change. In line with the above, I also wrote about goals this week. The trigger was a popular post (in Dutch) stating that because the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are unrealistic, instead of aiming for them, working towards them, we can better focus on getting in place’ enablers.’

There is a flaw in this thinking, a considerable flaw. Translated and summarised:

Are the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, unrealistic?

The SDGs together share a vision of the future. That vision is not fixed, but I interpret this as a pursuit of inclusive human development within the limits of the earth. The seventeen SDGs translate this vision into concrete goals. Collins and Porras named these types of targets BHAGs, big, hairy, audacious goals. A successful BHAG scares you a bit; it might just be achievable if you give it your all. A global end to poverty, for example.

The combination of vision and hairy goals provides direction and urgency. I notice this in practice when I work with people who put the goals to practice in their lives and organization. All those doers are fully aware that it is unrealistic that they achieve the goals on their own. But they believe in the vision and are energized by the concrete change that the goals are pursuing. The size of the goals also makes it clear that they are not alone. The contribution people make in their neighborhood, in their own way, is becoming so much greater than it could ever have been without the SDGs.

Conditions, “enablers,” play a role in this process. If vision and goals are the why to get moving, conditions are about the how. “With respect for everything that lives,” for example. Like values, these kinds of conditions are about what people consider important and what behavior is acceptable or not. That varies from community to community and can be a cause for conflict.

Imposing conditions creates endless discussions that distract from the work that is really needed. Are we doing the donut or broad prosperity? Do we approach the planet animistically or holistically? Every choice in this excludes people. This can be a plus for organizations. It helps in the selection process for new colleagues or partners. A global agenda like the SDGs does not have that luxury. We can only achieve this if everyone can and may participate.

The SDGs may be unrealistic, and that’s a good thing. It is really unrealistic to expect all people and organizations who put their weight behind them to contribute to the same conditions.

Without a doubt, both cases are well-intentioned. They may be signs of the framework age, where we have learned to believe that if the methodology is theoretically right, the outcomes will be alright.

It’s a bit — or rather, exactly — like a facilitator sticking to the program even if their group moves in a different direction. “That is a wonderful point, but let’s first get our definitions straight.” My wife, who is a gazillion times smarter at this than I am, always says that when working with a group, you have to make a plan and throw it away. It has become one of my mottos whenever working with people. Also, when it is about where to go next and how to get there.

A definition is a description, as exciting as the little blurb next to a Netflix title (but more informative). A vision is a story about the future that energizes a group of people. Goals are reminders of how much work you still need to do, ideally uncomfortable. Values (akin to the ‘enablers’ in the post) describe the attitudes and behavior that is or isn’t acceptable. They can exist alongside each other, complement each other, but never replace each other.

This is strategy as much as storytelling. A good story talks about change. There is a before and an after. A story is not a list of characteristics or a description. A story encourages people to act, reflect, individually, or collectively.

For instance, the American Dream, as a story. The story is that whatever your circumstances, you can become a success. It is a vision, mostly untrue and unattainable. Still, it encourages countless people each day to try to be different, try to be better.

What is a museum, then? I’d say that a museum is a place of abundance and attention where you can study the world in all its dimensions and — by extension — yourself to become a better person.

And the SDGs? The SDGs are a global commitment to make the future better for everyone, our planet included, through collective action.

Thanks for reading this update all the way to the end! It’s unbelievable this was only the second week of the year. Ordinarily, now my schedule would begin to slowly fill up. It’s been packed for the past 2 weeks, on top of a little bit of homeschooling, etcetera. So, there are tons of things to discuss next week or the one after. Thanks again, stay safe, talk soon!

— Jasper